WILDLIFE

Climate change impacts everyone, and wildlife is not an exception.

The impacts that are likely to be felt, like warmer temperatures and more winter precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, significantly impact the wildlife in Western Montana.

While the list below is certainly not an exhaustive list of impacted animals, it does provide a snapshot of the wide-range of species that will be forced to adapt due to climatic variation.

The impacts that are likely to be felt, like warmer temperatures and more winter precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, significantly impact the wildlife in Western Montana.

While the list below is certainly not an exhaustive list of impacted animals, it does provide a snapshot of the wide-range of species that will be forced to adapt due to climatic variation.

Wolverine

|

Montana, and especially Glacier National Park, is home to the largest population of wolverines in the lower 48 states.

It is believed that only 300 or so wolverines remain in the lower 48. The wolverine’s large paws and cold tolerance make it well-adapted to travelling in the snow. It’s important to note that female wolverines only build dens in the snow, making them vulnerable to the shrinking spring snow pack that we will see with the changing climate. |

Photo by Josh Leonard

|

For more information on Wolverines from Montana Audubon, visit here.

trout

|

Missoula's trout need plenty of cold water in streams and rivers to survive the hot summer.

Climate change means less precipitation falls as snow, leading to low water levels in rivers in later summer. Hotter air temperatures lead to hotter water temperatures, which lead to lower amounts of dissolved oxygen. Warmer waters and less available oxygen can stress and even kill trout. Overall, climate change is predicted to destroy a significant portion of trout habitat, likely impacting Missoula's sport fishing industry as well. Climate impacts on trout may mean new regulations for anglers, and more "hoot owl" closures (where fishing is closed in the afternoon). |

Photo by Carlos Scheidegger

|

For more on trout and climate change, read the Clark Fork Coalition's report "Low Flows, Hot Trout." or read the a report from the Natural Resources Defense Council, "Trout in Trouble"

clark's nutcracker

|

This robin-sized jay survives on pine seeds in high-elevation subalpine forests near Missoula.

Its success is tied to healthy subalpine forests, especially whitebark pine forests in the Missoula area, for seeds for winter food. Resulting from warmer temperatures in the winter, pine bark beetles are able to overwinter in a way that they never could before, decimating whitebark pine ecosystems. Between this beetle and white pine blister rust, the trees that the Clark’s Nutcracker uses as food sources are experiencing a serious decline. Models suggest that this species will be gone from the Missoula area by 2080, although it may persist in higher-altitude locations. |

Photo by Jerry Ting

|

snowshoe hare

|

Snowshoe hares are uniquely adapted to their seasonally-changing habitat. They grow a grey coat in the summer, and white in the winter to better blend into snowy surroundings.

Their coat color change is precisely aligned with historic seasons. As climate change shortens winters in Montana, snowshoe hare's white coats are mismatched with their surroundings, putting them at increased risk for predation in early spring and late fall. Additionally, their large back paws make them especially well-suited for snowy environments. |

Photo by Loren Mooney

|

sage-grouse

|

While not found in Missoula, the sage-grouse is still an iconic Montana Bird.

The survival of the greater sage-grouse is dependent on large expanses of sagebrush habitat, making it a "sagebrush obligate" (a category including pronghorn antelope and many other bird species). Expanses of sagebrush that used to cover parts of the Great Plains have been fragmented by development, especially for oil and gas extraction. Climate change poses additional threats to the sagebrush ecosystem. |

Photo by Steve Jones

|

To learn more about sage-grouse, listen to the podcast series "Grouse" by Boise State Public Radio.

ECOSYSTEMS

Climate change will cause rising temperatures, reduced snowpack, and shifting patterns of streamflow.

Together, these outcomes will cause variations in humidity, soil moisture, and water availability - all of which play key roles in determining the success of an ecosystem.

Every ecosystem is impacted differently; explore below some of the specific impacts in some of Western Montana’s most iconic & beloved ecosystems.

Together, these outcomes will cause variations in humidity, soil moisture, and water availability - all of which play key roles in determining the success of an ecosystem.

Every ecosystem is impacted differently; explore below some of the specific impacts in some of Western Montana’s most iconic & beloved ecosystems.

Sagebrush

|

Photo by Josie Morway

|

The expanses of sagebrush plains that cover much of Montana and the Great Plains are uniquely vulnerable to climate change.

Cheatgrass incursion, hastened by warmer temperatures, threatens sagebrush habitat. Sagebrush, unlike cheatgrass and other annual species, can't regrow quickly after forest fires. Climate change's effects - including hotter and drier summers - will likely lead to more frequent and more severe fires in sagebrush and sagebrush/grassland ecosystems. |

Riparian Areas

|

Riparian, or riverbank ecosystems are defined by their dependence on water in lakes, streams, and rivers.

With climate change, more of Montana's precipitation will fall as rain, leading to lower snowpack levels, and lower water levels in summer. Lower summer flows seem likely to destroy and degrade riparian habitat. Some researchers, however, have suggested that riparian ecosystems, which already cope with extreme seasonal variation, may be well suited to adapt to climate change. |

Photo from Montana Trout Unlimited

|

alpine meadows

|

Found at the tops of mountains above the treeline, the elevation at which cold temperatures and long-lasting snowpack stop trees from growing, alpine meadows shelter unique species of plants and animals.

As temperatures warm and snowpack decreases, trees are able to grow at higher altitudes, causing alpine meadow ecosystems to shrink or simply disappear. As this habitat vanishes, species dependent upon it, like bighorn sheep and pika, are threatened. |

Photo by Stephanie Pluscht

|

Pine Forests

|

Photo by Karen Mallonee

|

The effects of pine bark beetles, which can only be killed by extended cold winter temperatures, have begun to change the appearance of Western pine forests.

White pine blister rust, a recently-introduced pathogen, also poses a danger to whitebark pine forests in the Missoula area. More frequent and more severe forest fires also will likely change pine forest ecosystems, although the exact effects are not clear. |

Read more about the uncertain future of whitebark pine forests here.

RECREATION

New weather patterns may decrease snowfall, cause earlier peak runoff, and reduce river flow, disrupting the recreation industry that depends on nature: skiing, snowboarding, mountain/rock/ice climbing, rafting, kayaking, canoeing, fly fishing, birding, and more.

In Montana, outdoor recreation generates 71,000 direct jobs, $2.2 billion in wages and salaries, and $286 million in tax revenue. Climate change jeopardizes the very outdoor recreation activities that bolster our local economy.

Climate change is causing Montana’s winters to become warmer and wetter and summers to become hotter and drier.

Since tourism in Montana is a $2.2 billion dollar industry responsible for tens of thousands of jobs, a changing climate will have serious consequences for our state’s economy.

If you’d like to read more about how climate change is impacting Montana’s Outdoor Economy, read this report by the Montana Wildlife Federation.

In Montana, outdoor recreation generates 71,000 direct jobs, $2.2 billion in wages and salaries, and $286 million in tax revenue. Climate change jeopardizes the very outdoor recreation activities that bolster our local economy.

Climate change is causing Montana’s winters to become warmer and wetter and summers to become hotter and drier.

Since tourism in Montana is a $2.2 billion dollar industry responsible for tens of thousands of jobs, a changing climate will have serious consequences for our state’s economy.

If you’d like to read more about how climate change is impacting Montana’s Outdoor Economy, read this report by the Montana Wildlife Federation.

angling

|

With storms being more frequent and more powerful, polluted runoff will increase from urban and agricultural areas, picking up pollutants from the landscape and carrying them to nearby streams.

These pollutants enter the food web and compromise the health of many species, including the fish species we cast for, and the prey they consume. Additional runoff will cause increased sediment levels, lower amounts of dissolved oxygen, both of which are detrimental to the health of trout. Decreased snowpack will result in lower water levels for rivers in streams. Shallower water warms up more quickly, and warm water has less dissolved oxygen than cold water. All living things require oxygen, including aquatic species. Without adequate levels of dissolved oxygen, fish and insects understandably suffer. |

Photo by Mark Teasdale

|

To learn more about the confluence of fishing and climate change, read this article by the National Wildlife Federation and this resource page from Trout Unlimited.

Paddling

|

Photo from University of Montana Campus Recreation

|

Boating, as we know it is an activity that is incredibly vulnerable to changes in hydrologic conditions that may be disrupted by climate change.

Rising temperatures will cause more precipitation to fall as rain rather than snow, reducing the natural reservoir that feeds our rivers through drier summer months. With decreased snowpack, there will be less runoff to feed our rivers in the spring, causing river levels to be lower, and rapids to be smaller. More frequent and more powerful storms will increase polluted runoff from urban and agricultural areas, picking up pollutants and carrying them directly to our rivers. |

To read more about paddling and climate change, visit here.

Skiing

|

With skiing, it’s simple; more days of snow mean more days of skiing.

With more winter precipitation expected to fall as rain instead of snow, our winters are expected to look quite different. 23.5 million Americans participated in winter outdoor recreation in the winter of 2015-16. In the western United States, studies find a strong positive correlation between skier visits and snowfall. Considering that we’re expecting to see less snow in coming winters, opportunities to ski and the revenue produced from skiing will decline. Here, snow is tied directly to money and jobs. Less snow will physically and financially challenge ski areas in Western Montana. |

Photo by Matt Burt

|

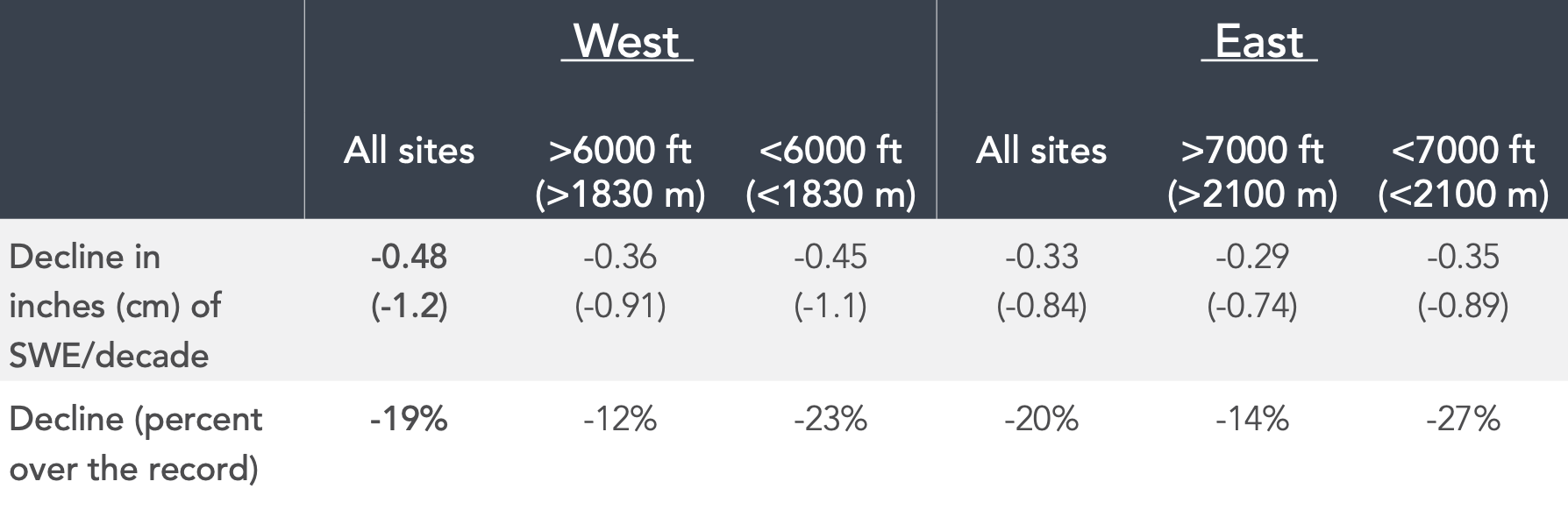

The table below illustrates Montana trends (east and west of the continental divide) in April 1st SWE (Snow Water Equivalent) from 1935 to 2015. This information highlights the long-term downward trends in snowpack on April 1st. This decreased snowpack is most pronounced at lower elevations. In general, April 1st snow water equivalent has declined about 19% in the last 8 or so decades.

From the 2017 Montana Climate Assessment

To read more about the economic contributions of winter sports, read this report by POW and REI.

To read more about the changing climate and skiing, read this article from NOAA.

To read more about the changing climate and skiing, read this article from NOAA.

Birding

|

Photo by John Quine

|

Climate change impacts the phenology (otherwise known as the timing of life history events) for birds, many of which follow a calendar based on internal and external cues.

Shifting temperatures and precipitation patterns can alter the timing for migratory species arriving back to breeding grounds, which can pose a problem if, for example, a bird returns to a nest still covered in snow. Here in the Rocky Mountains, robins, the quintessential harbingers of spring, now arrive two weeks earlier than they did a decade ago. Can they adapt? We hope so. Climate change also impacts snowpack levels, which in turn affects river temperatures and oxygen levels. All aquatic invertebrates need oxygen, and many require specific water temperatures to survive. Eagles, ospreys, and insectivorous birds rely on a healthy aquatic food web for survival. |